The Haterade Lost its Taste

Remember that part in Return of the Jedi when Luke is wailing on Darth Vader and Darth Sidious is like “gooooooood, let the hate flow through you”. I can’t deny, morally grandstand as I may, that being a hater feels good. It’s fun! But what really doesn’t feel good is when I have even the most microscopic investment in the target of someone’s hate. Then it feels really bad.

You’ve heard the Teddy Roosevelt quote a thousand times before, yet it still bears revisiting:

What is a Hater?

My first draft of this essay failed to define what I mean by the word “hater”. It also failed to establish why that’s a bad thing. So, some throat-clearing is in order.

People have various reasons for disliking things, some quite universally valid and some less so (read on to the next sections to see what I mean). Sometimes, out of a very basic human desire to be heard, we tell other people what we dislike and why. Sometimes we even do this on public fora.

Humans often accidentally develop habits via repeated practice. Our brain is a reinforcement learner, the source of many of our greatest achievements (science) and greatest weaknesses (addiction). One becomes a “hater” when one reinforces a habit of expressing their moral and aesthetic preferences primarily via negativity rather than positivity. Defining one’s self by what one is not, rather than what one is.

This is inefficient, uninteresting, and kills the vibe. Consider two interactions where your opinions mismatch:

A: Joe says they like something -> But you don’t like that thing.

B: Joe says they hate something -> But you like that thing.

Does A or B feel worse? For me it’s B hands down, on a gradient depending on how vicious Joe is with his attacks. Likewise, it feels a little lame to respond to A by saying “ummmmm ackshually I don’t like that and here’s why”. People who disagree about things can coexist just fine, we don’t have to litigate every subject under the sun until we’ve arrived at the perfect objective truth that everyone must believe.

Haters are more likely to start B interactions, and more likely to escalate A interactions into arguments/invalidations. They are not pleasant to interact with. Everyone can be a hater a tiny bit of the time, sure. But being negative in general is corrosive to your community and your friendships.

My biggest problem with this tenor of negativity is that it muddles discussion with unnecessary pedantry. Your average hackernews thread1 is dominated by people attacking non-loadbearing claims and/or arguing over matters of taste. This gnat-straining is boring noise that isn’t accomplishing what the commenters think it is.

Whence the Hater?

I’ve been known to read a spot of history and some older books from time to time. I’m no expert on the past, but I spend more time thinking about it than is healthy. I’ve heard it said that grousing about the current and rising generations is a tradition that stretches back millennia, with even Aristophanes complaining of the Sophist kiddos:

I’m not quite sure we can equate these old curmudgeons with the modern man. The sense I get from my studies is that the while the people of the past had plenty to complain about, they were more ready to accept issues as beyond their grasp and outside their purview, the realm of God and the king. They were on balance less questioning of tradition, more willing to subordinate themselves to authority, and generally defined themselves by what they loved rather than what they opposed. When they did lodge strong and contentious critique, it was almost always framed as restoring some natural and correct preëxisting order rather than progressive innovation or new identity formation.

Something radically changed in the last couple centuries. The kings (and to a lesser extent, the gods) have greatly receded. Markets have proven themselves to be a very efficient way to allocate labor and goods to fulfill human preferences. Democracy has emerged as a way for us to choose who leads us. The internet has connected everybody everywhere with instantaneous communication—yes, even the miserable and authoritarian countries like Afghanistan. In a world without kings or subjects, a new form of mankind has arisen: the voter, the consumer, homo economicus. Suddenly, your peasant opinion matters. Your opinion is in fact deadly serious.

In liberal democracies with market economies, structures of domination have partly given way to structures of influence. Aside from a few inelastic necessities, nobody can make you buy anything, and nobody can make you vote for anyone either, they can only hope to convince you to do so (through advertising and propoganda). That doesn’t mean they don’t try their best to constrain your choices, whether via oligopolies or oligarchic parties. But the power ultimately always rests with the individual, acting in concert with other individuals, voting with their feet and with their wallet. I suppose this is a good way to arrange society and prevent tyranny, by spreading power diffusely among everyday folk.

But it sure makes them uppity!

Consumers have deeply internalized the power they hold, to the point they don’t even think about it consciously any more. It comes perfectly naturally to them: criticize shortcomings, demand improvements, threaten to take your money elsewhere. Online I see people do this all the time and state that they’re taking some brave anti-consumerist stance. This an odd thing to claim while you’re exemplifying the essence of consumerism. Same thing for electoral politics, except it’s their elected politician instead of their chosen product and their vote instead of their money. And then they claim to be weary with our hopelessly corrupt government. Sir, you are engaging in the exact kind of civic participation that keeps it marginally more honest!

Our markets and our democracies would shudder and collapse if everyone just stopped. Stopped voting, stopped purchasing. Or even just stopped caring so much about how they were voting or purchasing, picking products and candidates at random. The power held by the people is what has created this wonder-world of technology and freedoms, and letting it go would be unadvisable.

My hypothesis: haterism always begins as the simple act of embracing and echoing strong negative opinions about things that you feel influence your life for the worse, as way of warning and consensus building. What could be more human than this?

I’m Retired

I tend to keep most of my opinions to myself these days when it comes to brands and culture wars. I see commenters commenting and I just think “there but for the grace of God go I”. By my own definition I am lazily—even hypocritically—opting out of the information-aggregation systems that have made my world so rich and easily navigable. I don’t leave google reviews for restaurants, I don’t comment in reddit threads, I’ve failed to turn my vote in for almost every national election I’ve been eligible for (this one has more to do with the fact that I’m embittered that the electoral college makes my vote worth way less than it could be under a national system). I am not lacking in opinions, but I just don’t want to pay the costs social and otherwise for blasting them out frequently and publicly. We live in an increasingly multi-polar world where there’s no clear cross-institutional hegemony to cozy up to or rage against, so no matter what stance I take I’m guaranteed to alienate some people and close some doors. Why take a stance if there’s only downside?

There’s something to be said for moral courage here. Martin Luther King Jr and the Civil Rights movement paid heavy personal costs to accomplish what they did. But maybe that’s too straightforward: they paid a price and won the world something in return. What about the thousands of protestors in Iran who paid the ultimate price to fight back against tyrannical inhumanity? Maybe it’s too soon to tell, but from here it seems like the uprising was doomed from the start. They were unarmed protestors facing against a regime completely unbothered by gunning down its own citizens. Is it callous to call their sacrifice wasteful? Has anything been accomplished?

Maybe every effort is a gamble. The time you spend filling out and delivering your ballot is a gamble that your vote is the deciding one, which would be enormous upside for very little downside. When you take to the streets in Isfahan to chant anti-government slogans, you are gambling your life on the hope that the military will grow a conscience or your death will provoke international outrage and further weaken the regime. That would be an enormous downside for an unclear amount of upside. Does the marginal protestor, the marginal unjust death even move the needle? But did the marginal civil rights protestor in the US move the needle either? Does the protestor about to march to her death ever even think along these consequentialist lines? Don’t we call this sort of reasoning cowardice?

These are the questions that keep me up at night. I can’t even be bothered to leave reviews to support local businesses and inform fellow consumers—which seems like an obviously helpful thing to do—while there are people losing their lives right now for obviously moral—if not necessarily pragmatic—causes.2 This is a clear blemish on my character. I feel like I need to fix this.

But there is still something that gives me pause, that stops me from rushing off to sign up for Reddit and begin weighing in on the various pressing issues at hand: which robo-vacuum you should buy, whether ICE is an authoritarian paramilitary, how we should all feel about various far-flung geopolitical developments. The thing that stops me is reading the other comments. Some of these people seem kinda miserable, and they make me feel kinda miserable!

Hater Psychology

Let’s ease up on the weighty moral questions for a second and attack this from a different angle. Why does moral outrage feel so good in the moment and so bad in the aggregate? No, that’s still too hefty. Why does it feel easier to criticize than to praise?

I spend a good portion of my time online in an artistic community. Who knows why, since I lack the required skills to fully participate. But I like to think I have pretty good taste, that I have an analytical mind that can identify what makes things visually appealing and what makes them muddy or ugly. And yet, when somebody posts something they’ve worked on, what they’re doing wrong is so much easier to identify and verbalize than what they’re doing right.

When a kid is being annoying, it’s easy to snap at them and tell them why they’re so annoying. It is much more difficult to remember to praise them when they’re acting positively angelic.

Why could this be?

Theory 1: Aggregation Effects

What if objectively “good” things only really work in aggregate? Conversely, this would mean you only really need one “bad” thing to disrupt harmony and weaken the effects of the good. One might compare it to a gearbox: no number of good gears can make up for one bad gear.

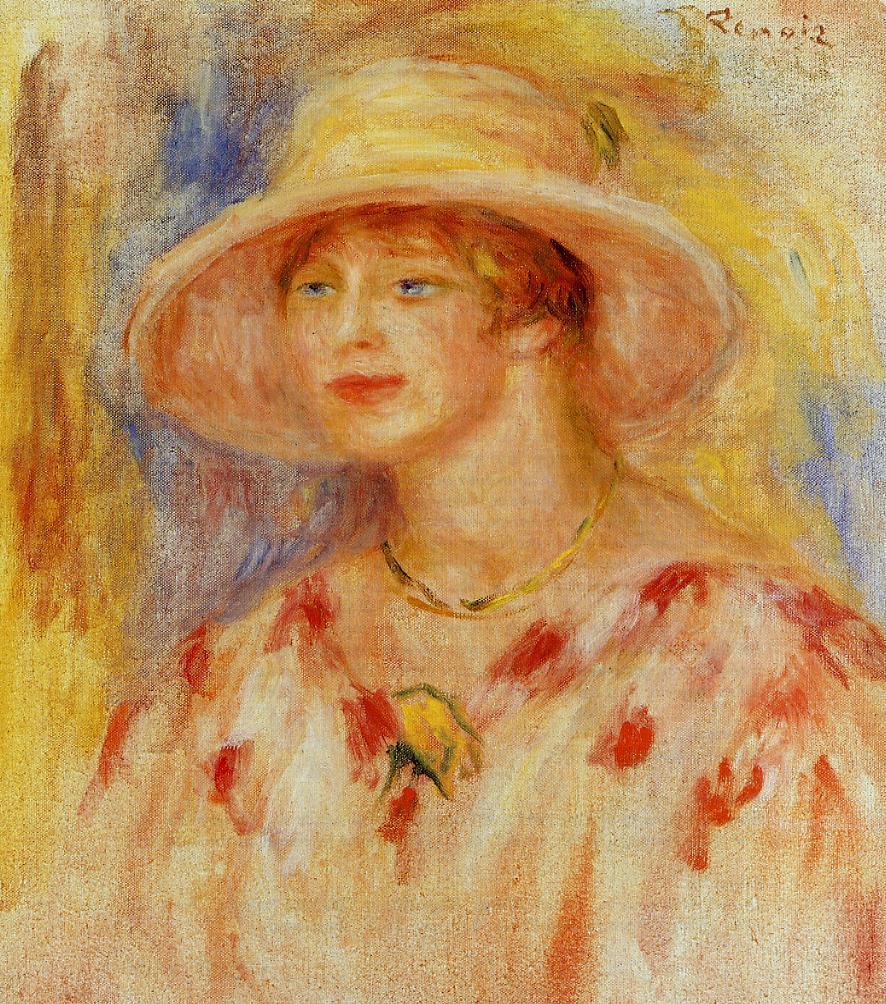

Under this framing, flaws in visual art are distracting and overcome its good qualities. I had an art history teacher once admit he couldn’t really enjoy Renoir for all of his beautiful use of color and light because his poor grasp of anatomy was so distracting.

In his defense, the weird faces come later in his career. Also he had terrible arthritis.

Eliezer Yudkowsky says something similar in his Twelve Virtues of Rationality:

I find this idea to be a bit depressing. How can any human expect to live such that their many virtues outshine their few vices? How can any flawed person reason so perfectly that they arrive at correct conclusions when our chaotic world and our own psychology is working overtime against us to deprive us of the clean data and dead-neutral analysis necessary to get there?

Of course, aggregation cuts both ways. The scientific method was built to counteract this exact problem, by requiring findings to be reproducible across settings and persons. Imperfect people can magnify their positive impact and minimize their negative impact by pledging themselves to aggregate causes and corrective mechanisms greater than themselves: a country’s constitution, a charity’s charter, a church’s commandments.

Regardless, this fails to explain situations where the good and bad things are very weakly connected, such that it would be bizarre to suggest one ought to necessarily occlude the other. Someone might criticize a head of state for failing to promote the arts when their track record on agricultural policy is very good. Does lack of funding for the arts completely wipe away the wins in agriculture? Does learning some deep dark personal secret about your favorite actor mean that their great performances are actually all bad? I think not.

Theory 2: Compulsion to Build

Indulge me in a little self quotation from my previous article:

Chaos rules the universe. It will only grow in influence until all matter and energy reaches a state of perfect entropy, where nothing will be recognized as being or doing anything in particular, leaving just a homogenous slurry of cold matter. What humans have inexorably done—especially in the modern era—is viciously fight against this. Where once there was rocks and plants, you raised a house. When your floor got dusty, you swept it. When a weed grew between two paving stones, you pulled it. When a tsunami came to wash it all away, you built it again. Where once disorder and anarchy and poverty reigned, you built a nation, a shared cultural identity, a language, a career.

In this framing, the artistic flaw is the weed between the paving stones. Every bit of your genetic programming screams that it must be destroyed because the alternative is Desolation from The Course of Empire—nature returning to take what is hers.

And maybe a little bit of “Destruction” beforehand, as a treat.

We must be nitpickers because the nits will take over if they are not picked!!!

This theory fails to resonate too strongly with me because I feel I can tell an equally compelling story in the other direction.

Theory 3: Compulsion to Destroy

Building, creating, organizing—it’s hard. It’s much easier and therefore more fun to undo. A master could labor for decades over a sculpture, but it would take me less than a minute to send it back to entropic dust with a little well-placed C4. And we love explosions, don’t we folks.

The tendency toward criticism is just a generalization of this power imbalance. We settle into modes of complaint and anger because they’re a local minimum that offers the best psychic reward-to-effort ratio.

So says Anton Ego in Ratatouille:

It’s cool to build a beautiful palace in Minecraft, but it’s so fun and easy to blow it up with TNT. Just a tiny fraction of the time and thought.

There’s also an imbalance of risk and power. Anybody who sticks their neck out with a claim or a creation is opening themself up to criticism and commentary, often at great personal cost. The best creators pour their heart and soul out so much that they begin to identify with their creations. But now an attack on their creation is an attack on them, even if the critic doesn’t wish it to be that way. So why spend time making something for everyone to mock when you could be the one having a grand old time doing the mocking!

Theory 4: Pure Memetic Fitness

In the EEA, rage was a very useful emotion. The consequences for false positives (oops I accidentally exiled someone who I thought was stealing food) were often less selectionally detrimental than false negatives (oops I accidentally trusted a food thief and now we’re all gonna starve). So the human brain evolved to prioritize negative arousal, to relentlessly seek it just like the modern man seeks fatty foods to make it through a cold winter that will never come. Historically this has not been a big deal because there’s only so much rage you could milk out of your immediate community and the trickle of news from the outside world.

Then we gave everyone a series of tubes they could use to beam enraging things right into your eyes. Some say this had the effect of atomizing us and dissolving our meatspace communities since our particular tastes could be algorithmically catered to, lessening the need to depend on each other for information, entertainment, connection. Bereft of built-in meaning, we seek causes to champion to fill that hole. The village festival has been replaced by the viral trend, especially the ones that make you mad for whatever reason.

Better minds than I have spoken extensively on this subject. In Toxoplasma of Rage, buried among Scott Alexander’s typical cutting insights is an observation that his maximally inflammatory posts—the ones tagged “Things I Will Regret Posting” as well as “Race/Gender”—outperform the rest of the top ten tags combined. He is incentivized and rewarded to make his readers want to argue with him. Why would you ever say something in a cool and levelheaded way when you could bait more engagement by saying it in an annoying way instead?

CGP Grey distills memetics to the cutesy metaphor of “thought-germs” in This Video Will Make You Angry. The internet is a place where enraging memes (remember! not the funny kind, the Dawkins kind) get iterated upon and spread at maximum velocity. You are once again just a tiny paper boat tossed upon the raging seas of evolutionary psychology.

Classy Criticism

If you think the purpose of this essay is to argue that nobody should criticize anything ever, you need to read it again. I am not advocating for toxic positivity, and it’s clear that consumer rage is a healthy immune reaction that keeps innovation alive and democracy intact. But I think people increasingly fall into a pattern where they can compose negative comments without running even the most basic cost-benefit analysis.

Humans want to be heard. They want to complain. This is not something you will be able to excise from yourself any time soon, maybe ever.

Some of your complaints are important and useful information. Posting “This restaurant gave me food poisoning and I saw a rat scurry under the table!” to a review aggregator is a good idea. This is Category 1.

But some of your complaints are just bad things happening to you, pure matters of taste, mistakes made by other people, etc. This is Category 2. In these situations, we all need a designated person to tank all of our whining: a spouse, a parent, a sibling, a best friend, a therapist. Maybe we even can rotate who it is every once in a while to give them a break. Venting and then letting people vent to you are vital ways to release built up pressure created by the many injustices of life. It could be the only thing stopping someone from snapping and building a Killdozer.

Category 1 probably belongs on the internet, in the public eye. Category 2 does not. Talk to your designated complaint tank.

Negativity is alluring and seductive. I have been guilty of getting into arguments on the internet. I have been guilty of broadcasting nonconstructive negativity. I created a Goodreads after my mission because I wanted to sharpen my media literacy. Reading is great, but analysis of what you just read is where the real neuronal activation occurs. To my horror, I have found myself really looking forward to penning my negative reviews. This is not good for the soul. A 3/5 rating should rightfully spend no more than 40% of the time on criticism, but that’s not how it often shook out. I must be stronger than this.

There are ways you can push your gut-reaction takes from Category 2 into Category 1, but it takes some work.

Step 1: Are you critiquing something effortful and worthy of critique? Or are you arguing against someone else’s Category 2 opinion? Unless you’re aiming to become their (bad) e-therapist, this is not worth anybody’s time. If you still insist on engaging, you may yet make yourself helpful by attempting to calm them down and sharpen their opinions. Try the Socratic Method instead of deploying a take of your own.

Step 2: Run a cost-benefit analysis to see if anyone could possibly profit from reading your opinions, which requires them to not just be effortful but at least somewhat novel to your reader. Originality is a tall order these days. If you can trace the pedigree of your insight to someone else’s work you saw online, consider whether your reader may have already seen the same thing.

Step 3: Be honest with yourself: can you deploy enough tact to possibly be persuasive to someone who doesn’t already agree with you? This is something redditors and twitterers are especially bad at. They don’t generally seem to be interested in persuasion, mostly “yes and”-ing and/or dunking. It will probably make you feel good to score rhetorical points against someone or connect over a shared gripe, but it will make the world a worse place.

Step 4: At all times, remember and honor the human effort and investment behind the subject of your criticism. If you want to call a work of media cringe, consider if you are such a callous person that you would be able to say it to the author’s face. If you want to write off a corporation or brand as irredeemably evil, don’t forget about the many well-intentioned humans who count on that employer to put food on their table. Do this cool empathy exercise where you pretend you are the subject of your criticism and see if you would enjoy hearing what you have to say.

Step 5: Strictly delineate matters of fact and matters of taste, and take care not to state matters of taste as obvious or objective. You can be way less careful about this when praising instead of criticizing.

At the end of this course of editing, you’ll hopefully have some pretty high quality Category 1 commentary that is worth publishing and will get people thinking. A great example of this is Noah Caldwell Gervais, who has done so much to change my opinions of video games I previously wrote off as mainstream slop by treating them as worthy of analysis.

Of course, you could also spend all that time creating something original for other people to criticize instead—a sort of Category 0. Were you to do that, I don’t really have any advice for how to get people to send Category 1 feedback your way instead of Category 2, sorry.

Phew, that was a lot of opinions. Am I a hypocrite? Well obviously yes, I’m only human. My essays are often posed as oppositional to some thought pattern I think is wrongheaded. I even titled this one “The Haterade Lost its Taste” instead of “The Sweet Sweetness of Love and Positivity”. I took my usual shots at reddit & twitter users. I spend a lot of my writing shadowboxing the criticisms I expect to come my way for the claims I’m making. I’ve heard it said one should not waste time addressing the concerns of the nitpickers, who despite your best efforts will find a reason to write you off anyway. It still causes me psychic damage to see someone identify a flaw (non-fatal, of course (:<) in my argument. But who can blame them, it’s fun to find flaws!

I wrote this essay for myself more than anyone else. The know-it-all is an unpleasant person to be around, but I find myself slipping into that role too often. I need to be more tolerant of inaccuracy, prioritizing people over purity. I’m swearing off that bitter Haterade!

1.

Hackernews is like a specialty reddit just for tech. People post technology-related links (mostly blog posts and news articles) and then discussion occurs in the comment thread. So what you’re seeing on hackernews is smart people reacting to someone’s work, often less charitably than they could. ↩

2.

I’ll have you know that I have in fact attended protests and carried signs (no I’m not going to tell you which ones, I don’t even know you) but when I self-reflect I feel like my motives were impure. My reasons for attending were tainted both by a desire to fit in and to signal my beliefs, which is selfish nonsense when the subject of the protest is pretty deadly serious and not at all about me! ↩