History is a Necessary Exercise in Psychological Distress

My wife recently took a weeklong work trip to New York City, so I got a chance to watch a show that wouldn’t play well with the usual crowd. I chose something that had long rotted on my list: Ken Burns’ magisterial Civil War miniseries. I don’t have any novel takes about it: it’s great. The confederate-sympathizer amateur historian guy has weird vibes but maybe he brings some needed perspective to offset the whole “victors writing history” phenomenon? Anyway you should watch it along with the rest of Ken Burns’ opus, enough said.

The emotion I mostly felt while learning about the privations and horrors of a domestic war was fear. I especially connected with the wartime diaries of the civilians left behind, enduring sieges and famines and other disastrous disruptions. A battlefield is of course hell on earth, but even a scenario where food disappears from shelves is so far out of distribution from anything I’ve experienced. This isn’t just a me thing, war and her unholy children of mass famine and plague are blessedly alien to most of the humans that have lived in the Pax Americana era of world history.

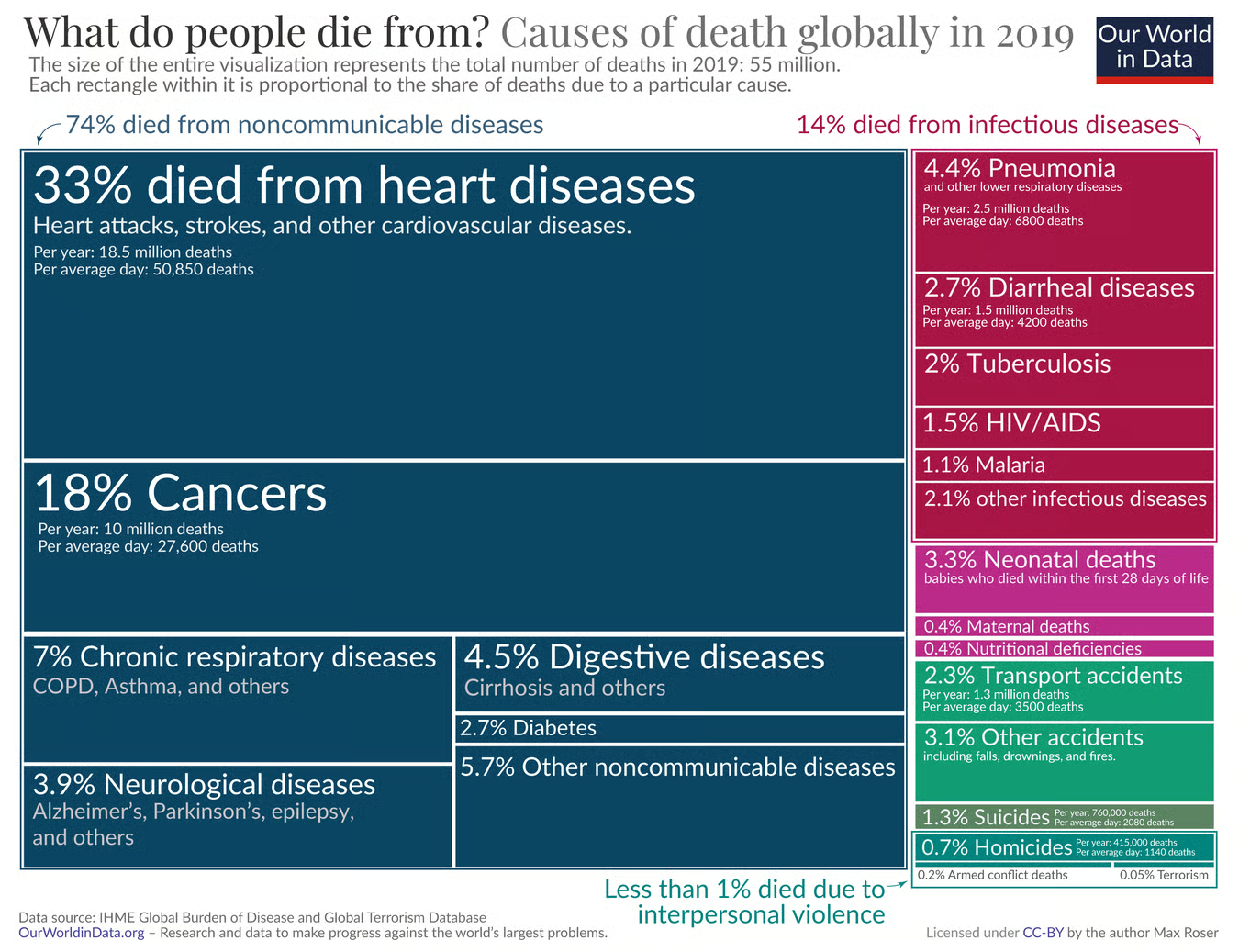

Yet there are people living right now who must be very hardy and calloused from repeated and sustained periods of bloodshed. They’re living in Syria and Iraq and Israel and Gaza and Ukraine and Sudan. There are mass casualty events all the time around the world where hundreds of people die in natural disasters or terrorist attacks. I ultimately learn about them on Wikipedia’s current events tab because American media doesn’t seem to deem them newsworthy. I’ve spoken before about how building your world model out of the media that finds you is inherently distortionary. I still believe that stronger than ever. Many people I have spoken with have a bizarre belief about how bad their world is. They are surprised when I report that crime is way down both in America and Europe over the last couple decades. They are unaware that they could have doubled any amount of money by simply parking it in any index fund before the pandemic. They have not realized that a growing proportion of mortality worldwide is of the peaceful “died of old age” type, rather than violence or infectious disease.

The violence and infectious disease categories used to be a lot bigger

One explanation—non-monocausal, weakly held, overly glib—I can come up with for this pessimism is that they caught terminal news brainrot—which of course predates social media brainrot by several decades—and have become addicted to subjecting themselves to an unending torrent of negativity. There’s a reason that a serious study of history does not involve reading the contemporary news of the era you’re learning about and taking it at face value. Scott Alexander proposes that a possible reason for the so-called “vibecession” is that conditions are worsening in the institutions and cultural centers where large amounts of our media is produced (specifically New York journalism and podcasts) and they’re spreading their misery to the wider public. But it’s just a guess.

Gratitude

On an individual psychological level, the literature on this is quite clear. To achieve happiness in the face of whatever environmental challenges you may be facing, your best shot is gratitude. But “just feel grateful bro” isn’t exactly actionable. What if there were some activity we could engage in that would proxy for—or even induce—gratitude?

I’m increasingly convinced that a heavy dose of academic history is the perfect prescription for both the depressed doomer and the unprepared over-optimist. The infinite—in both the quantitative and qualitative sense—nature of media in this unique moment has unfairly saturated our individual capabilities for ingesting evidence. If I am a 1000mL flask of information bandwidth, it feels to me like 800+ mL of that data is filled by content produced in the last 5 years. It leaves one with the sense that things are always going to be this way, have always been this way. I would say the most common sin in ahistorical discourse is noticing any trend and extrapolating it indefinitely into the future (or worse, indefinitely into the past). But the truth is that things have never been this way, and may never be this way again. Staring at numbers and charts isn’t sufficient to induce the required feeling of alienation. You need the moving power of narrative.

Unfortunately, the act of inviting an ideologue to look to the past often has the counterproductive effect of arming them with a bunch of new cherry-picked examples to toss out in arguments. There are no shortage of new-media voices willing to offer just-so analyses of history that conveniently justify all of your preëxisting biases. I’ve found traditional academic analytical history to be a discipline uniquely obsessed with credentials and dogmas, highly exclusionary of outsider commentators and heterodox opinions, sort of like how medicine is. Having seen how sloppy history can be wielded to lend legitimacy for any arbitrary purpose, I think I understand the dismissiveness of historians for what it truly is: an immune reaction to what would otherwise devolve into an entirely vibes-based discourse of no objective value.

You can reliably get your hands on a reputable exploration of some past era or event that you find interesting. Not only that, you can get an engaging, well composed account1. Not only that, you can get it for cheap or free! The supply of pop history has outpaced the demand or something. If you like reading novels but have never dipped your toe into nonfiction, I think you may be surprised how engrossing and well-paced it can be. And I think you will come away with an appreciation for how the world has ended up.

Accessible Entrypoint Recommendations

Film

I haven’t watched a ton of documentaries/docu-series, but you really can’t go wrong with Ken Burns.

Books

- Red Famine by Annie Applebaum

- Rubicon by Tom Holland (different guy than you’re thinking of)

- Joan of Arc by Helen Castor

- John Adams by David McCullough (or really anything by McCullough)

- Pre-Industrial Societies: Anatomy of the Pre-modern World by Patricia Crone

- History of the Peloponnesian War by Thucydides

Podcasts and Videos

- History of Rome by Mike Duncan

- Revolutions by Mike Duncan

- Hardcore History by Dan Carlin

- Sarah Paine Lectures on Dwarkesh Patel’s Channel

- Premodernist

- The Histories

- The Histocrat

- Sean Munger

Blogs

We all already know what’s going in this section. Say it with me:

A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry by Brett Devereaux

Historical Fiction

You can also get most of the way there by immersing yourself in the aesthetics of an alien historical era via moderately well researched fiction. Stuff like Ridley Scott films (Kingdom of Heaven, The Last Duel, Gladiator (but not the sequel)) or Hilary Mantel novels (Wolf Hall Trilogy, A Place of Greater Safety) or James Clavell novels (Shogun and the rest of the Asia Saga) can do a lot of legwork in introducing you to the vibes and foundational differences of past despite their shortcomings and inaccuracies.

Things Were Worse

The goal of this exercise is to understand deep in your bones that the comfy conditions of modernity are unnatural and fragile. Once you’ve cut across enough eras and sampled enough regions, you’ll start to pick up on the same patterns. Peace is not the default. Equality is not the default. You receiving the basic needs of life is not the default. The strong dominate the weak. Premodern life was shorter and scarier. You spent more time hungry, cold, exposed to the elements, threatened with violence. Magic and paganism were perfectly rational coping mechanisms in an unfeeling world where you were at the mercy of massive natural and political forces beyond your grasp or knowledge. A volcano could erupt in Indonesia and cause mass famine and political upheaval in Europe. A flooding river or a rampaging warlord could kill millions of nameless, forgotten Chinese peasants.

It wasn’t all bad. Most of the time you just did your duties, raised your family, worshipped your gods, celebrated your festivals. But there was the undercurrent of coercion: if you don’t pay up and stay in line, your liegelord will spoil your household to get what is owed. There was a lurking shadow of tragedy: your dead children buried in the backyard. There was the looming spectre of an inevitable future disaster: a plague, a bad harvest, a war.

Different eras and regions have their own flavors of suck. What I describe above applies to agrarian folk in hierarchical societies (which covers the vast majority of times and places) but even the industrial era replaced these fears and privations with an entire new set of horrors under early industrial capitalism. It really isn’t until the post-WWII era that we get a broad lasting peace and rapid rise of quality of life—unless you live in Southeast Asia, Korea, China, Zimbabwe, Rwanda, or the Middle East (or some other place I’m forgetting, apologies), in which case there were couple more decades of suffering before things mellow out.

Most people lived before Jonas Salk. They could just, you know, catch polio for no reason!

I think viewing the world in this way—anchoring yourself in a historical bedrock that demonstrates that humans and nature always arrange themselves in miserable ways without sustained negentropic effort—is transformative to your ways of thinking and being. It can both help you appreciate what you have and strengthen your determination to go without some luxuries. My house has some insulation and airflow problems, such that running the furnace is basically lighting cash on fire. So I avoid turning on the heat as much as I can stand. We’re lucky to live in a mild climate where our winter lows only get down to the low 40s fahrenheit, but it’s still pretty unpleasant waking up to a cold house. As I roll out of bed, my teeth a-chattering, I cast my mind back to how John Adams’ family would have experienced winter. With no central heating or fiberglass insulation, they would endure many months of bitter cold and dark with just heavy woolens and a fireplace. At least one of them would probably fall gravely ill. In the winter of 1770, his daughter Susanna would die before her second birthday from dysentery. For the time, that was actually a cutting edge high tech farmhouse! Maybe my chilly house isn’t all that bad.

Despite my best efforts to escape them I am still subjected to a lot of takes online. My main critique (completely in my head, actually starting a back-and-forth with the takesters is self-destructive behavior) these days that I am increasingly falling back to is: “This analysis is ahistorical”. Not every proposal needs to include some giant works-cited of historical material to justify it, but it seems like more and more commentators fail to personally integrate any historical context at all when thinking through problems of policy and pragmatics. Karl Marx and Adam Smith understood this, and supported their totalizing theories by applying them to historical events and demonstrating their explanatory power. You’ll often hear the word “unprecedented” used to describe contemporary political events in the United States, a country that literally had a civil war less than two centuries ago. Catastrophizing about how things are the worse they have ever been is counterproductive yes, but worse—it’s ahistorical.

At the tail end of a broad survey of human history I reckon you’ll feel thankful for what we have in the present2. It’s also natural to fear for what could be lost in the future. A third and equally important mind-state you should strive to arrive at is uncertainty. Almost nobody at any time in the past could have predicted what would come next. So nobody who claims to know the future with high confidence can be trusted. We the noble and uncertain must band together and muddle our way through this mess. The alternative is a world led by myopic arrogance, flitting from one crisis to the next. There are patterns to learn from and lessons to be had, but in the end what we can do right here and now is feel thankful, scared, and uncertain. And those are just scary names for the virtues of gratitude, meekness, and humility.

1.

My previous praise of academic historians notwithstanding, they don’t usually make incredible storytellers because there’s a lot more to the discipline of history than just the retelling of it. The highest quality narrative history often comes from authors that are not necessarily credentialed but pay appropriate deference to the academics doing the real work and soberly synthesize the facts without letting an agenda creep in. ↩

2.

If I may get a little personal, you should also learn about your family’s history. There really is something quite profound about the fact that every one of your ancestors’ decisions had some causal effect, for good or for ill, on where you ended up now. The most important decision of course being the one to have the child that would go on to be your next ancestor in the line. If any one of these people were to have done things differently it would reverberate through both you and your cousins’ lives. Maybe you’d live somewhere different, have a completely different set of friends, a different school. Maybe you would be fabulously wealthy or desperately poor. Maybe you would have never been born! Confucianism has the concept of 孝 (xiao), which we give the cutesy English translation of “filial piety”. Respect your elders type stuff. But it’s a pretty heavy idea. You simply would not exist without the procession of ancestors coming before you, all the way back to LUCA. You’re born with a preëxisting mortgage on your soul that you can only begin to pay off by honoring your elders and perpetuating their line. ↩